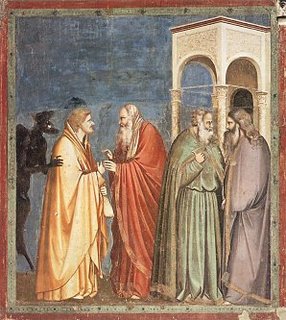

Judas's Dilemma, Giotto's Rendition

[Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337), Scenes from the Life of Christ: Judas’s Betrayal, 1304–06, Fresco]

Judas’s Dilemma, Giotto’s Rendition

In a small fresco panel at the end of the Scrovegni Chapel in Podova, Italy, Giotto painted an important turning point in the life of Christ. Judas, one of the twelve disciples, has made a promise to betray his master in exchange for 30 silver coins. In a sequential episode, Judas indicates Jesus by the kiss he gives him. Jesus is then arrested and crucified according to Roman custom. Seeing the arrest, Judas is besot with guilt, tries to return the coins to priests who refuse them. He then discards them on the floor of the temple, but they are recognized as “blood money,” collected and buried in the sinners’ graveyard. Judas hangs himself. As Giotto portrays this scene of betrayal, he has the character of Satan standing behind and guiding Judas. One might say that Judas is serving as agent for this shadow character who is visible to the painter but not to anyone of the figures within the painting itself. Thus, we witness Giotto’s telling of the story, a perspective that indicates that there are forces at work in the transaction which are in some ways beyond immediate human perception. Yet, they are all too human.

The shadow is Judas’s shadow. It is clearly attached solely to him. Though the rendering depicts a physical character, Judas is the true actor having internalized the shadow role he was to play. Logically, one would expect the satanic character to be present at the fulfillment of its wish. However, it is nowhere evident in the scene in which Judas kisses Jesus. It was not needed because that force was already foreshadowed in and contained within Judas’s promise made for compensation received. According to the Bible, we know that Satan was an adversary to the Christ, but was unwilling to attack directly. Satan (or Ahriman, or other names for the same archetype) instead operated as much as possible through the agency of others and in the shadows so to speak. Within this framework we are witness to a double transaction, the work of Satan through Judas, and the exchange of money for commitment or promise to the priests to act at a later date. An act of destiny was set in motion that would change the history of Western consciousness through the process of the crucifixion. A second associative pattern, connected to and reflected in this moment, is buried within a Christian ethic—that money and activities surrounding it are bad, or worse, evil and likely to corrupt faith and the spirit. The phrase “filthy lucre” has its origins in this ethic.

Giotto is famous for his having brought the art of representational rendering to a new level early in the Renaissance. His figures are not only columnar and dimensional, but also display their emotions and humanity. The Scrovegni Chapel is a very special venue for Giotto’s frescos because he was responsible for designing and painting the entire chapel—a rare moment in an artist’s life and an even rarer glimpse into an artist’s genius. What emerges is an extraordinary capacity for story telling and in that storytelling, a revelation of insight. In this one small fresco, Giotto has portrayed one of the mysteries of money—he has demonstrated how intention is transmitted through a financial transaction. In accepting the money, Judas was morally bound to the intentions of the priests who in themselves could or would not directly identify Jesus, probably for political reasons. Satan also had an intention aligned with the officials, but also could not act directly. The money itself was buried in the earth to eventually return to base mineral; it had served its purpose as medium and transmitter of intention. Judas, in taking his own life, was relieved of physical body in time and space, and returned to the spirit having served for better or worse. While this very Christian story casts aspersion on the financial transaction, it is also true that positive intentions are conveyed through the same mechanisms for the benefit of all parties involved. In its rightful place money is a servant, not a tyrant. And, every transaction is part of an unfolding story.

John Bloom © 2006

1 Comments:

Would you not want to revise this blog in view of the developing translation of the Gospel according to Judas?

Post a Comment

<< Home